Photography by Steven LaChance

I woke in the night, taking a moment to adjust my eyes to the darkness of the room. A faint light filtered through the windows, casting fleeting shadows whenever a car passed on the street below. Hearing movement, I sat up in bed and glanced around, but there was nothing to see. I lay back down, attempting to regain my senses as another car rolled by. I took slow, deep breaths—which usually helped soothe my anxiety. New nights in unfamiliar places were always challenging for me, and this first night was no exception. I heard another noise in the room; sitting up again, I looked around but found nothing. Then the shadows danced once more, and that’s when I caught my first glimpse of him. He stood barefoot in the far corner, arms wrapped tightly around himself as if giving himself a hug.

“Sie haben unsere Schuhe mitgenommen,” he said, speaking in German—a language I didn’t understand.

“What? I’m sorry, I don’t…” I stammered, trying to clarify.

“They took our shoes,” he interrupted, continuing in English.

“Who are you?” I asked, confused and a little frightened.

“I am David,” he replied.

In an instant, it was over, leaving me bewildered and unsure of what to think. Was it a nightmare even though it felt too real to be a dream. That was our first night in the Leopoldstadt district of Vienna, Austria.

We had journeyed to Austria from Hungary the day before, where we had been staying in Budapest. Our train ride from Budapest to Vienna took place in a cozy carriage that felt like something from an old movie. The cubicles, separated by wooden doors from the main aisle, featured two sofas facing each other and a curtained window revealing scenic countryside views. It truly resembled a scene from a classic film. The conductor walked the aisle, entering cubicles to verify tickets. I was taken aback when he suddenly opened our door to check our tickets. I wondered whether he was still known as a conductor or if his title had evolved into something like ticket inspector instead. Of course, I wouldn’t ask him that, so when he checked my ticket, I smiled and offered a quick “thank you” instead of addressing him as “Mr. Conductor.” The wooden door closed, and he continued on his way.

As I gazed out the window while we traveled, my husband Rick sat beside me, already drifting off, his head nodding in rhythm with the train. We were leaving Budapest, and I felt relieved at our departure. It was April 2022, during a period of heightened tension in Hungary. The political climate felt hostile, and this discomfort was evident as we navigated the streets of Budapest. People appeared dissatisfied and distrustful of one another. We had met another gay couple living there who shared their experiences and described the worsening situation for the queer community. Their sorrow was palpable as they recounted the hatred and their treatment as second-class citizens. They spoke of hate crimes, and an oppressive fear seemed to loom over every step taken in the city. Articulating the pervasive oppression in a city and country is challenging, but it resonates—heavy and mournful. So, indeed, I embraced the prospect of leaving Budapest behind, resolving not to return anytime soon.

The train journey was both enjoyable and calming. I have always cherished train travel, particularly in Europe, where the experience is enriched with diverse options—from high-speed trains to the classic style we relished on our trip to Vienna. As the countryside zipped by, I was struck by how similar many places can look each time I gazed out the train window. You could be anywhere in the world, yet the scenery might be nearly identical. This realization often renders man-made borders nonsensical in my eyes. The world wasn’t meant to be separated like livestock on a chart. It is vast and inherently intricate, and it shouldn’t be reduced to mere territories and isolation. When you explore the world, you quickly learn that the similarities between places often overshadow their differences, making them feel as familiar as your own backyard.

After just over three hours by train, we arrived at Wien Hauptbahnhof, the central station in Vienna. One of the great advantages of train travel is how effortlessly you can disembark and continue on your way. You simply collect your luggage, and you’re off. It was a delightful spring day when we emerged from the station to find a black sedan waiting for us. I’ve always found it amusing that most transportation options from airports or train stations in Europe tend to be black sedans. In contrast, where we live in the Yucatán, Mexico, white is the preferred color to keep vehicles cooler. Color certainly plays a role. Nonetheless, our driver greeted us in a customary black sedan— a Mercedes—ensuring a comfortable journey. I enjoy the experience of being chauffeured. As a child, I thought it was glamorous to have a driver who opened and closed doors for you. Honestly, I still find it exciting, though I’ve never quite reached the level of glamour I once imagined it would be. I recall once being picked up in a black stretch limousine in New York City, but that glamour was short-lived when navigating Brooklyn traffic became quite terrifying. There’s nothing glamorous about praying to make it to Manhattan in one piece. However, this ride was speedy, comfortable, and soothing.

Vienna is a magnificent city ready for exploration. As the capital of Austria, it is renowned for its captivating beauty, blending historical architecture with a vibrant cultural scene. Its artistic spirit is underscored by landmarks like the Baroque Schönbrunn Palace and the Gothic St. Stephen’s Cathedral. Peaceful parks and gardens, including Stadt Park, offer serene retreats. Additionally, Vienna is famous for its delightful coffeehouses and lively café culture. In terms of cuisine, local specialties such as Wiener schnitzel, sausages, and Sacher torte highlight the city’s culinary gems. Vienna indeed possesses remarkable qualities that are hard to rival, earning its reputation as one of the most breathtaking destinations in Europe and beyond. We would spend two wonderful weeks there, savoring this extraordinary city.

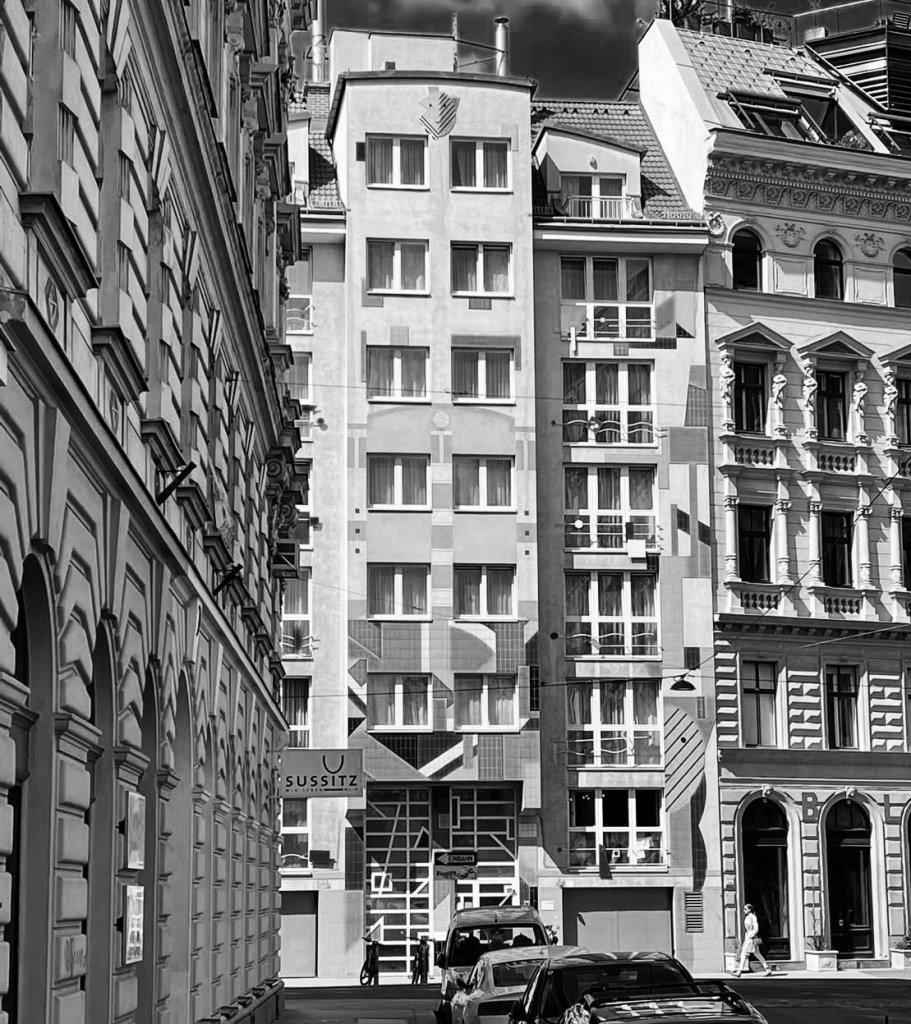

We soon arrived at the apartment building where we would be staying. From the outside, the building felt somewhat out of place among its surroundings. The building’s façade showcased a vibrant metalwork design with geometric patterns, embodying a unique modernist style.

We were on the fifth floor of the building. Although the apartment was compact, it contained everything necessary for us to feel at home. It was both clean and comfortable, with the highlight being a wall of windows that overlooked Leopoldstadt.

The first morning, we were welcomed by both of us, ready for coffee and a bagel. The first night’s strange encounter remained, still running through my mind in an attempt to make some sense out of it or to define it. I told my husband Rick about the experience, and he admitted he too had difficulty sleeping. He said he thought he kept hearing someone fiddling with the front doorknob and strange noises within the room. I asked him if he thought it might be because of the area our apartment was located in?

“Well, if you mean because of the war, this building appears as if it were built after the war. It looks more like something from the sixties. Of course, there is no telling what was here before—given all the bombing,” he said, thinking aloud while sipping his coffee.

He was right. The building did resemble those constructed after the war. Looking out the window over Leopoldstadt, I noticed both structures that were clearly post-war and others that had been painstakingly repaired after the bombings. Many of these restored buildings featured modern roofs atop classic brick facades. The architecture was striking. I stood by the window, admiring a stylish roof across the street. As I gazed down the street, I watched the neighborhood awaken with people bustling about. One younger Hasidic Jewish man caught my eye as he rode his bicycle, creating an interesting contrast with the classic surroundings. I also observed numerous men wearing black hats, suits, beards, and sidelocks. The women were dressed very conservatively in dark colors. Some had their heads covered—most commonly with scarves.

I turned to Rick and said, “This is a very Jewish neighborhood,” as I pointed out the scene below.

With the strange event of the night before and this new knowledge, my interest was piqued. Out of curiosity, I began researching and exploring Leopoldstadt and uncovering its history from before and after the war. I learned that Leopoldstadt had been recognized as the heart of the Jewish community since the late 1600s. Unfortunately, that prominence significantly declined during World War II.

On a dark November night in 1938, the Nazi regime initiated Kristallnacht—also known as the “Night of Broken Glass”—in Leopoldstadt and across Germany and Austria. This event marked a night of violence and destruction fueled by state-sponsored terror. Synagogues burned, Jewish businesses were vandalized, cemeteries were desecrated, and police and firefighters stood by, ordered to do nothing. Hundreds of Jews were killed, and about 30,000 Jewish men were arrested and sent to concentration camps like Dachau and Buchenwald. The brutality of that night shattered lives and marked a turning point for the Jewish community, as families realized there was no future for them under the regime’s oppression.

We knew nothing of Leopoldstadt’s history when we had arrived at the apartment, but given the restless night we both endured, it all made a strange kind of sense. As our time in Leopoldstadt went on, the strange occurrences persisted for both of us. For me, the nightly visitations from the figure in the shadows named David would continue. Rick would wake each morning feeling a deep sadness and fatigue, as if the weight of the place bore down on him. Given that he had studied Judaism and his two daughters—my stepdaughters—were Jewish, I wasn’t surprised by his feelings at all. They seemed to make a complete logical sense in a situation which seemingly defied any sort of true and provable logic.

The impact of what the Nazis did to the Jews in this neighborhood lingered on every corner and with every step. One night, as we returned home, we passed a seemingly ordinary building—just a brick structure with few windows. Inside, a rabbi could be heard singing prayers, met with responses from his congregation. Outside, military personnel stood guard in uniform, armed with automatic weapons to protect those who gathered to pray.

We often overlook the fact that anti-Semitism remains very much alive today, as exemplified by this sad reality. No one should ever need protection to practice their chosen faith, regardless of what that faith may be. This also clarified why the disturbing history felt so present within these walls and streets. It was not merely a relic of the past; hate was still active here. Though it may be concealed, it still posed a real and credible threat to those involved.

As you walk through Leopoldstadt, you’ll notice brass plates embedded in the sidewalks in front of various buildings. These plates honor the Holocaust victims who once lived there, marking the tragic fates they faced due to Nazi hate. Known as Stolpersteine, or “stumbling stones,” these memorials consist of brass plates affixed to concrete cubes, commemorating the lives lost during the Holocaust. German artist Gunter Demnig initiated this project in 1992, designing these small tributes to be placed outside the last-known residence or workplace of the individuals. Today, there are over 70,000 Stolpersteine throughout Europe, with over 400 located in Leopoldstadt alone. This figure isn’t surprising, given Leopoldstadt was historically a district heavily populated by Jewish residents before the war.

Before the Nazis gained power in Austria, Jewish people made up forty percent of the local population. Jewish theatres, coffee houses, schools, synagogues, and prayer houses thrived until everything was abruptly annihilated. Jewish men, women, and children lost their rights, possessions, and, in many cases, their lives if they failed to escape in time. Leopoldstadt was not an exception, and the Jewish people felt betrayed by their neighbors who participated in the hateful atrocities or simply looked the other way.

The stumbling stones throughout Leopoldstadt tell the story of the weight of the atrocity and the loss. However, when I looked at the ground at the entrance of our building—where our apartment was located—I saw no Stolperstein commemorating those who might have been lost. It appeared that nothing had happened in this location of any significance or important recollection. However, every night, for the entire two weeks we stayed there, the strange occurrences replayed over and over—never revealing more than the haunting message: “They took our shoes,” and “I am David.” Rick continued waking up with a heavy sense of sadness—a feeling that stayed with him until we left the apartment for the day only to return once again upon him waking the next morning. He often described it as a heaviness he could not easily shake.

Time moved on quickly, and our last morning in Vienna had arrived, and we were prepared to leave. We left the apartment building with our suitcases, waiting for the car to arrive. It didn’t take long before a black sedan pulled up to take us to the airport. The driver jumped from the front seat and opened the trunk to take our luggage. I handed him my bag first and stepped back, waiting for Rick to do the same and for the driver to open the doors. I looked down at my feet and, just in front of the apartment building—closer to the edge of the sidewalk than the doorway—lay a Stolperstein. We had missed this all along for some reason. It was for the building where we had been staying. I stood there, reading the plaque with tears in my eyes and a chill running through my body.

The plaque read:

IN MEMORY OF THE 30 JEWISH WOMEN AND MEN, AND THE 6 CHILDREN WHO LIVED IN THIS HOUSE AND WERE DEPORTED AND MURDERED BY THE NAZIS.

FRANZISKA HACKER

November 14, 1895

DEPORTED TO THERESIENSTADT IN 1942, MURDERED IN AUSCHWITZ IN OCTOBER 1944

KOLOMAN HACKER

March 8, 1896

DEPORTED TO THERESIENSTADT IN 1942, DEPORTED TO AUSCHWITZ IN 1944, DIED IN DACHAU ON JANUARY 18, 1945

MAX HACKER

February 26, 1938

DEPORTED TO THERESIENSTADT IN 1942, MURDERED IN AUSCHWITZ IN OCTOBER 1944

MINDLA BOOKFÜHRER

June 16, 1878

DEPORTED IN 1941 TO OPOLE DURING THE HOLOCAUST MURDERED

I was puzzled that only four names were on the plaque, leaving out the many others who had lived there, yet it clearly conveyed the fate of all. If David had lived there, he would have been one of the many unnamed. I glanced down and snapped a quick photo with my phone to share with Rick once I got in the car.

As the driver approached and opened the door for me, I looked up to see an old rabbi across the street. He looked intense, with a white beard, a black hat, and dressed fully in a black suit and coat. He was watching me intently. Our eyes met directly in the moment. Tears filled his eyes, and mine mirrored his. We held that gaze for a brief moment before I entered the car, and the driver closed the door. There was a connection of energy that went between the rabbi and myself that I could not explain. It was one of those mysteriously profound moments, I didn’t want it to end until I had committed it to memory.

I watched the rabbi as we drove away, peering out the back window. He stood there, stoic, tears still glistening in his eyes, until he faded from view as we turned off the street.

I can’t fully articulate the many emotions I felt at that moment. There were so many. Sometimes, during profound experiences like these, words fail to capture the essence of what you think—and maybe the emotions are what we are meant to carry and remember. A sensory memory instead of one that is entirely visual. Whatever transpired in those final moments in Leopoldstadt resonated deeply, and I will hold onto it until my last breath—and perhaps beyond, into whatever lies after. The rabbi? You may ask, was he really there, or was I tuning into something from the past? Was he a ghost? I can’t answer those questions with any certainty because I saw him clearly, and he seemed to be very solid and physical in appearance in every way. Ghost, spirit, or angel? I don’t think so, even though a strong connection was evident between us. For whatever reason, at that moment in time, we were connected. It is as simple as that, and I can offer no further explanation.

History is a living entity. Our actions toward others leave an enduring imprint on the places and things we touch. The emotions from such events linger, along with an unspoken energy for those still residing among those memories. Maybe that was the lesson I was supposed to take away from my time in Leopoldstadt. Perhaps that is what the old sad rabbi was trying to convey to me with tears in his eyes, that the sadness lingers and does not fade, at least not for him and at least not for Leopoldstadt.

Copyright 2025. Steven LaChance, all rights reserved.

Leave a comment