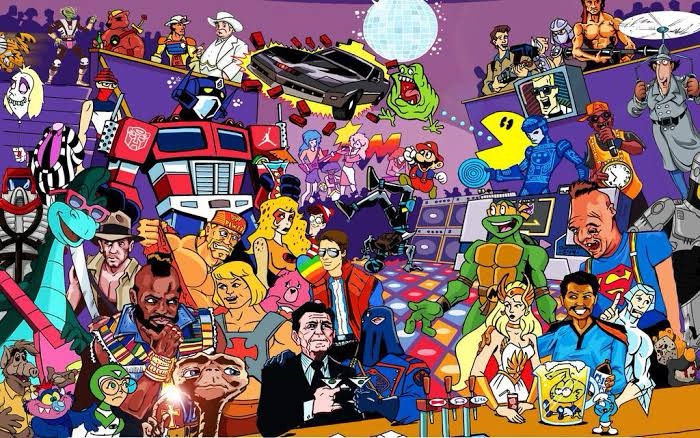

It was 1982, and I was seventeen—carefree, bold, and utterly convinced that the future was bright. I remember walking into the local arcade with my pink polo collar flipped up and starched, my straight-leg jeans perfectly faded, and my loafers polished just enough to look effortlessly cool. A typical seventeen-year-old in the eighties, caught somewhere between childhood and the threshold of adulthood, still believing the world was mine for the taking. I dropped some change into the jukebox, and as the needle set down, Kim Wilde’s Kids in America burst forth, filling the space with an energy that perfectly captured the era. I moved over to the Space Invaders machine, immersed in the simple thrill of the game, the soundtrack of my life echoing in the background.

Back then, everything seemed so simple. We were a generation untouched by the harsh realities that lurked beyond our small-town borders. We had no time for worries—only the immediate joy of a good song or a high score. That time was innocent, a period marked by the unbridled optimism of youth. We believed in the promise of tomorrow, unburdened by the weight of the world.

Yet, when I reflect on those days now, the nostalgia is bittersweet. The bubble of protection we lived in was, in many ways, an illusion. Outside that arcade, the world was unraveling.

Unemployment in America hovered at 10.8%, and a severe recession threatened the very fabric of society. Entire towns, like Times Beach, Missouri, were being evacuated due to toxic contamination. And then there were the tragedies—random acts of violence that should have shattered any illusion of safety.

By 1982, doctors were seeing more and more cases of a strange, deadly illness primarily affecting gay men. At the time, it didn’t even have an official name. People called it the gay cancer or GRID—Gay-Related Immune Deficiency—before it was formally recognized as Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome, or AIDS. It was spreading fast, but no one really knew how or why. Fear turned into stigma. The media barely covered it, and when they did, it was often with cruel undertones. The government ignored it, pretending it wasn’t happening. Those who suffered were shunned, abandoned, left to die in isolation. I was seventeen, living in my small-town Midwest bubble, unaware that an entire community was being devastated, that a generation of men just a little older than me were already losing their lives while the rest of the world looked away.

In August of that year, a 13-year-old girl named Lisa Ann Millican was abducted from a shopping mall in Rome, Georgia. Her captors, Alvin and Judith Neelley, tortured her in an Alabama motel room for days. Judith injected her with Drano and Liquid Plumber, trying to kill her slowly and painfully, before finally ending her life with a gunshot. Her body was discarded like garbage off a cliff. At the time, I never heard her name.

Earlier that summer, in Michigan, a 27-year-old Chinese American man named Vincent Chin went out to celebrate his upcoming wedding. He never made it to the altar. That night, he was brutally beaten by two white autoworkers, Ronald Ebens and his stepson Michael Nitz, who blamed Japanese car manufacturers for the decline of the American auto industry. They mistook Chin for Japanese and took out their frustrations on him, striking him repeatedly in the head with a baseball bat until his skull cracked open. He died four days later in the hospital. His killers never spent a day in prison.

On a hot August morning in Miami, Carl Robert Brown, a 51-year-old schoolteacher, walked into a welding shop with a shotgun. He had argued with the shop’s employees the day before over a repair bill. The next morning, he returned, killing eight people before being shot down by a passing motorcyclist as he tried to flee. Weeks earlier, Brown had been evaluated for psychiatric issues but wasn’t deemed a danger.

And then there was Washington, D.C., on a cold January day, when Air Florida Flight 90 crashed into the icy Potomac River after failing to de-ice properly before takeoff. Seventy-eight people lost their lives, some drowning in the frozen water while others remained trapped inside the sinking plane. The same day, a Washington Metro train derailed, killing three more. The city was thrown into chaos, two disasters unfolding almost simultaneously.

But we didn’t see it. Or maybe we did, and we just didn’t understand. The world outside our own felt so distant, like something that happened to other people in other places. We heard the news in passing, maybe caught glimpses of tragedy in the evening reports, but it didn’t touch our daily lives. Our biggest concerns were which song to play next, which arcade machine had the best graphics, or if we’d saved up enough for a weekend movie. That was the bliss of youth—the ability to exist so completely in the moment that nothing else seemed to matter.

Now, looking back, I realize how much was happening just beyond my line of sight. How many people were suffering, struggling, fighting battles I couldn’t begin to comprehend at the time. How many warnings were there, how many cracks in the façade, even in our own backyard? Maybe the world wasn’t really better or safer back then—maybe we were just too young to notice the danger.

We were the Kids in America, just like the song said, too busy with our own small joys to recognize that history was already shaping the world we’d grow into. Now, that world feels heavier, more complicated, and the weight of awareness makes it impossible to ever return to that same kind of innocence. But maybe that’s the price of growing up—the moment you realize that nostalgia isn’t about longing for a time that was better, but for a version of yourself who simply didn’t know any better.

Leave a comment